After a decade of disruption in urban transportation, Uber has finally gone public.

The company has been the highest valued tech IPO since Alibaba and Facebook, and is one of the main highlights among the wave of Silicon Valley unicorns going public this year.

But in the end, Uber’s IPO was a bumpy ride.

As its public offering closed in, the ride-hailing startup’s valuation began to slip, finally settling on US$45 per share, the lower end of the expected range between US$44 to US$50.

This puts its valuation at about US$75.46 billion, which is a 38% drop from its initial US$120 billion valuation late last year.

Uber’s low valuation comes as it met with setbacks of data scandals, the fatal car crash in Arizona, as well as Uber driver demonstrations 2 days before their IPO.

Besides, Uber’s competitor Lyft market debut in March has not been smooth. The shares tumbled over 20% since its debut and plunged to US$56.11 on April 15, 35% below its first trading day highs and 22% below its IPO price.

That’s not all. Lyft has also reported a loss of US$1.14 billion for the first quarter, a sharp increase from the loss of US$234.3 million in 2018.

Similarly, it also hasn’t been very good for Uber.

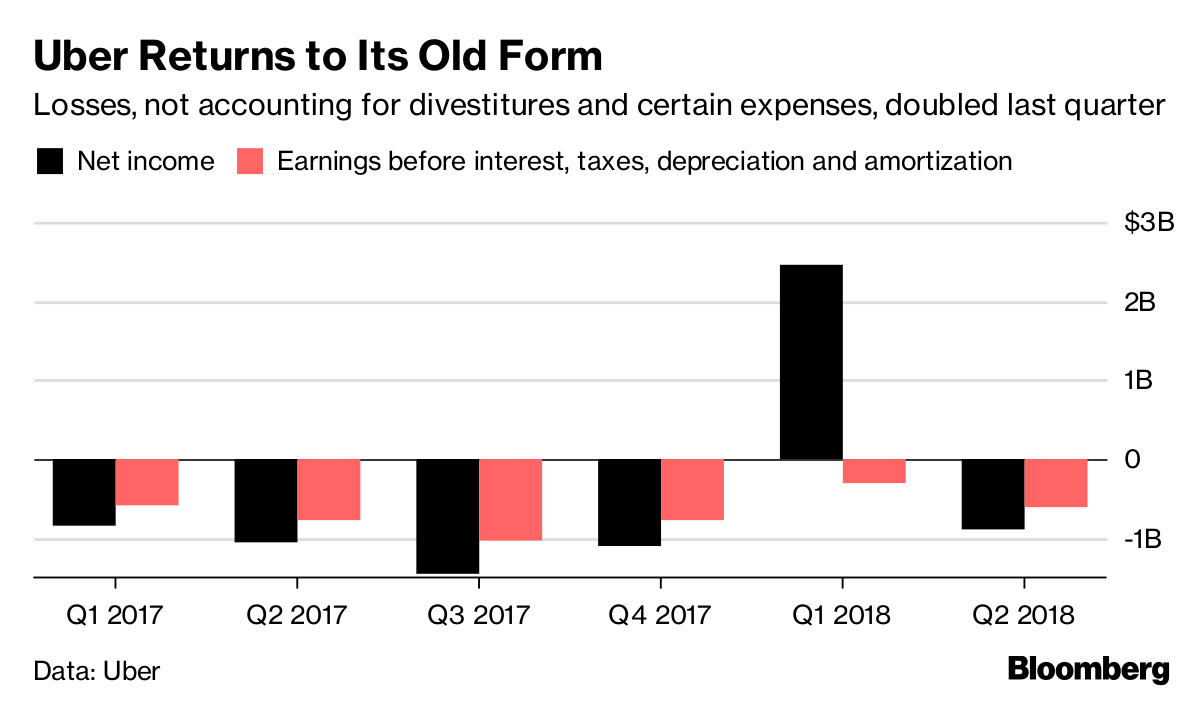

If you look closely at the financial structure of Uber, while the company’s income indeed rose 43% to reach US$11.3 billion in 2018, it has never recorded a net profit.

“To be absolutely practical, a lot of these startups are not going to start making money within a 10-year period,” said Sze-Hui Goh, a partner at Evershed Harry Elias to BusinessTimes.

These companies need a longer run, and more than ever a solid business model if they want to display a positive company performance in the future.

You see, this situation in Amazon which while going public, still recorded losses. However, its growth was high and now the ecommerce company has exceeded a US$1 trillion market cap.

But still, investors have to remain cautious and attentive when it comes to ride-hailing. Because, in terms of fundamentals, these companies are still handing in a red report card.

The same goes for China’s Didi Chuxing, Southeast Asia’s Grab and Go-Jek, India’s Ola, the Middle East’s Careem and Russia’s Yandex have been burning cash at an impressive rate while showing little or even negative operating leverage.

A decade after ride-hailing services were first launched, they makeup just 0.4% of total vehicle miles traveled in the US and indeed much lower elsewhere.

The Atlantic magazine noted in a recent opinion piece that, “Uber almost doesn’t feel like a business, but rather some essential service that investors believe should exist, so they have kept injecting money into it.”

Okay, so enough with the backstory. With Uber and Lyft now public, what does this mean for Grab and Go-Jek in Southeast Asia?

Well, it is a reality check for the Southeast Asian unicorns when it comes to their turn to follow Uber and Lyft steps to becoming public companies.

With the conservative pricing in the initial public offering for Uber, on top of the lackluster stock market performance for Lyft – this could encourage venture funds to rethink their investments in the future.

“In general, startup valuations have been stretched especially at an early stage. This is a good reflection on how valuations normalize as money becomes more scarce,” Rachel Lau, the managing partner at Malaysian investment firm RHL Ventures told BusinessTimes.

“What people will be more concerned about is startups’ performance versus valuation; and whether their performance is consistent… There is likely to be a pullback once the market becomes fatigued with companies without strong profit fundamentals,” she added.

Startups simply have to find a way to make money before going public, especially amidst the public capital market being skeptical of the profitability of ride-hailing companies.

But profits aside, publicity is also equally important. These companies also have to take the right business strategy and signal to investors of a positive clean image.

But for now, it looks like both startups are more focused on stepping up competition with each other for market share rather than considering IPO.

So far, Grab CEO and Co-founder Anthony Tan said that Grab is not going to be listed anytime soon, even though the startup is already a decacorn with a valuation above US$10 billion.

“We will continue exploring potential strategic partners to invest further into Grab. IPOs are not needed in the near future,” Anthony Tan said in Jakarta on March 6.

Go-Jek also stands in line with Grab as it mentioned that IPO is not a top priority for the startup at the moment. The company instead, is more focused on strengthening its application and services in Indonesia and other targeted countries for expansion.

One point that makes a difference between these Southeast Asian ride-hailing apps is their movement towards becoming a superapp.

Unlike Uber which focuses solely on ride-hailing, Grab and Go-Jek have expanded beyond ride-hailing and are trying to create a comprehensive superapp that offers customers everything from food delivery to financial services.

However, when you have the same or similar cars and mostly the same drivers, riders will use whichever service that is cheapest. Almost everyone will have both apps on their phones, and when it comes to choosing, the decision is often made based on which is the cheapest or offers the most discounts.

There’s no brand distinction between Grab and Go-Jek, and things such as loyalty card points are definitely not enough to differentiate one ride-hailing service from another, they need to bring it out from the battle of prices.

In the end, coming to IPO. It is ultimately not just for branding or more capital, rather it is an objective market test for a startup’s true valuation and potential.

So let’s look forward to the development of these ride-hailing unicorns and see which company is going to be the first in figuring out that successful business model.

Leave a Reply